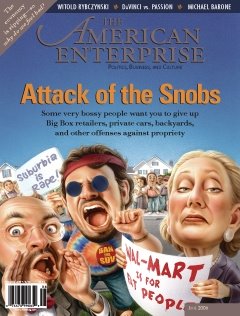

There are some absolutely killer articles in this month's The American Enterprise devoted to Wal-Mart and "sprawl."

There are some absolutely killer articles in this month's The American Enterprise devoted to Wal-Mart and "sprawl." First, Karl Zinsmeister has an article entitled "In Praise of Ordinary Choices." Zinsmeister sums up very nicely the nexus between liberal academic elites, "smart growth," and opposition to Wal-Mart. I especially like the lines "many of the activists now militating against suburbia, against 'Big Box' retailers, against roadbuilding. 'I got mine, now pull up the ladder' snobs are a dime a dozen in these movements, and much of the leadership is supplied by fanatical ideologues who rail against the very idea of single-family homes, private cars, an energy-based economy, and even green lawns" and "elite control of urban aesthetics." That is a perfect description of both PARD and No SuperWalMart.

I strongly urge reading the whole article to get a real understanding of what's going on in Pullman and Moscow right now.

The problem with most writing about cities is that people go out and say, "Here's what I like." And the corollary to that is usually, "This is what cities ought to be." Urban historians have tended to share certain tastes common to a Northeastern city-dwelling elite, and have been too hasty to dismiss other choices.Technorati Tags: wal-mart walmart

Urban history traditionally has been about elites at the very center. It's an almost exclusive focus. How can academics be so uninterested in where the vast majority of people live? What kind of amazing blinkered vision could produce this?

The academic world has cared about only a few parts of the city. That is so narrow-minded, and also counterproductive--because it says the actions of most of the citizens most of the time are of no interest.

--Robert Bruegmann

Robert Bruegmann, author of the fascinating essay on "suburban sprawl" that starts on page 16 of this issue of The American Enterprise, is an unmarried art history professor living in an apartment tower in Chicago. Bruegmann does not have a deck, grill on an industrial-size barbecue, spend weekends riding a John Deere mower, or bear any other vested interest that would make him a defensive apologist for American suburbia. He is just a smart person who is curious about how the real world operates, who observes carefully, and who shows respect for the billions of small judgments made by ordinary citizens in the course of their daily lives--choices which have cumulatively created the complex "horizontal" communities that most Americans now call home.

Our sprawling urban areas, like many other aspects of our current life, are quite different from counterparts in previous centuries. The transformation of our cities makes some temperamental conservatives (who are often not the same people as political conservatives) unhappy. And some unease is understandable: Like all changes, America's dramatically evolved new living patterns have weaknesses as well as strengths.

But Americans who honestly compare their home environments to those of the previous Depression/WWII generation will instantly acknowledge that the overall trends have much improved the average family's welfare. Most Baby Boomers grew up in small houses on concrete slabs, with children stacked up in bunks in a couple of bedrooms, and an entire family typically sharing one bathroom. Nobody had much private interior space. City kids had no yards, lots of noise, pollution, and other urban hazards. Elderly urbanites often ended up in deteriorating row houses or fortress apartment towers. Only a small slice of the population dreamed of airy kitchens, high-ceilinged family rooms, libraries and media centers, basement rec centers, backyard pools, and quiet shady streets.

Americans today have a wide range of choices: Cul-de-sac? Condo? Farmhouse? Townhome? And on something as intimate as where and how you live, choice is precious. For many of us, there is no single permanent "right" answer for housing--preferences can change dramatically according to our age and phase of life. Moreover, community options need to vary to accommodate all sorts of incomes, tastes, and household sizes. So a riot of different living styles like what is now available in the typical U.S. metropolis--an onion with layers reaching from center-city lofts way out to exurban horse farms--offers rare opportunities for individual satisfaction.

This issue of The American Enterprise is our small attempt to help keep the nation's living options wide open. For organized disdain toward today's horizontal communities is on the rise. In many places there is fierce animus toward new homebuilding. There are wars over transportation and shopping alternatives. The job-siting decisions that undergird today's new forms of scattered living can spark resistance.

Again, let's be fair and admit that a certain amount of disorientation and worry is understandable. Many of our new community structures have popped up almost overnight. When I was a child few people had ever heard of a covenanted homeowner's association or condominium. Home Depot and Target and Ikea stores did not exist. Our family--like most--owned just one car. Like a new hedge which has grown at breakneck speed, suburban America needs trimming and tending and nurturing in plenty of places. So most of us would welcome a sensible, positive, productive effort to reduce suburbia's frustrations, and eyesores, and overflow costs. Sure: let's improve and beautify and streamline the new forms.

But "sensible, positive, and productive" are not words that describe many of the activists now militating against suburbia, against "Big Box" retailers, against roadbuilding."I got mine, now pull up the ladder" snobs are a dime a dozen in these movements, and much of the leadership is supplied by fanatical ideologues who rail against the very idea of single-family homes, private cars, an energy-based economy, and even green lawns.

A prime example of what we are calling The Attack of the Snobs is today's effort to paint Wal-Mart as a diabolical plague. This is not some spontaneous popular wildfire (for the views of ordinary Americans toward Wal-Mart see pages 54-55), but rather a coordinated agitation ginned up in war rooms by professional partisans. It is the most expensive campaign ever waged against a corporation, with more than $25 million having been sunk so far (mostly by unions) to turn public opinion against multiple aspects of the formula that created the world's most efficient retailer.

I quickly count more than a dozen Web sites that beat on Wal-Mart full time. It's a regular terrarium of screamers: hel-mart.com, walmartvswomen.com, sprawl-busters.com, wakeupwalmart.com. The heaviest is Wal-Mart Watch--with 36 employees in Washington, D.C. and a fat budget--a prize project of the Service Employees International Union. It's run by a clutch of political hacks, including John Kerry's 2004 campaign manager and other Kerry and Democratic National Committee strategists. And the other biggest attack squad, WakeUpWalMart, is steered by the political adviser to Howard Dean's 2004 campaign. So give Wal-Mart credit for creating lots of high-paying jobs for otherwise unemployable individuals.

Hillary Clinton knows which way the wind blows. She served proudly and profitably on Wal-Mart's board for seven years, without any recorded objection or complaint. But as soon as the unions and anti-sprawlers went after the firm she flipped, returning a $5,000 contribution from Wal-Mart's political action committee "because of serious differences" with company practices. As is now de rigueur in any culture skirmish, a Michael Moore-style film has been produced, accusing Wal-Mart of every sin imaginable (except profligacy). Its Washington, D.C. premiere was hosted by the honorable pot stirrers George Miller (D-CA) and Ted Kennedy (D-MA).

We've seen this pattern before. Attack a high-flying corporation (preferably one a little naive about politics) and paint it as an agent of dangerous capitalism (or social harm, or toxic cultural or political views). Before Wal-Mart it was Microsoft, the drug companies, Halliburton; now it's Exxon.

Is it reasonable to vilify major American companies in this way? In any given week, 140 million people shop in a Wal-Mart store. Wal-Mart is our nation's leading employer. (There are 30 percent more people working under its roof than are serving in our Army, Navy, Air Force, Marine, and Coast Guard active-duty forces combined.) If Wal-Mart were a country, it would outrank all but 19 nations in economic size.

It's apparent that the recent attacks against Wal-Mart have seriously distracted the firm from its central task of becoming a more productive company. After powering upward for decades, the company's stock has fallen since the opposition campaign began (as I write, it's down 21 percent in two years). Instead of making the tough, gimlet-eyed decisions that cause a business to bloom, Wal-Mart's CEO now spends much of his time on PR sideshows, touting the introduction of organic carrots and other environmental sops, endorsing a minimum wage hike (irrelevant, since Wal-Mart's average starting wage is already almost twice the national minimum), and otherwise talking up motherhood and apple pie in an attempt to counteract bad media.

Wal-Mart has also had to set up a fat D.C. lobbying and public relations octopus to defend against the war rooms being run by the Kerry and Dean assassins and union activists. Until recently, Wal-Mart's lobbying budget was zero. Even after it finally hired its first D.C. representative, he was instructed to take lawmakers out to breakfast instead of dinner to minimize expenses. Now Wal-Mart has resorted to standard defensive lobbying and campaign contributions, and is throwing money at Michael Deaver and other malodorous "image consultants."

All of this is completely antithetical to the company's core philosophy of not wasting its customers' money on frou-frou. For reasons of thrift, company execs, including the CEO, have always shared hotel rooms when they travel. Wood-panelled offices and such are verboten, allowing the firm to spend less than half the industry average on administrative costs. Super Bowl tickets and free dinners from suppliers are always turned down--because such costs would ultimately work their way back into the price of goods. Alas, today's attack dogs are forcing Wal-Mart to become a more conventional company and unraveling some of the delightful idiosyncrasies that not only brought landmark economic success but also kept the firm close to its customers culturally.

Mind you, Wal-Mart's economic accomplishments add up to a whole lot more than just nickels and dimes. As the company gained strength in the national retailing scene over the last 20 years, productivity on the part of the trade in which it operates rose at an amazing 7.6 percent annually--two or three times as much productivity growth as in the rest of the economy. Economists calculate that because of its soaring efficiency, Wal-Mart singlehandedly reduced the overall cost of living in the U.S. by 3.1 percent. That amounts, on average, to $2,329 of extra cash available to every American family, every year.

Contrary to snotty stereotypes, the company has done this not by piling clip-on ties and plastic shoes ever deeper on the tabletops, but rather via intensive, inventive, high-tech management. Wal-Mart has pioneered new computerized supply management, inventory tracking, and transport processes that other companies all over the world have raced to emulate. In the process, it has cut huge amounts of wasted resources and squandered opportunities from the ancient process of bringing consumers the goods they want.

In the process, Wal-Mart has created a net 210,000 jobs that would not have existed absent the company, according to the best academic research. Studies show that local employment expands rather than contracts when a Wal-Mart opens in a community. And pay in the region does not suffer.

I will state for the record that I myself shop at Wal-Mart only infrequently. Not for philosophical reasons--I'm just not much into stores so big that you need track shoes and a bottle of Gatorade to walk through them. But even Americans who don't often take advantage of Wal-Mart directly, like me, still benefit from the company's thrift and creativity. Economists have found that any time there is a Wal-Mart in a region, prices in all the other stores within that region will average 13 percent lower for groceries, and 15 percent lower for drugstore goods.

And companies that can't match Wal-Mart's prices work energetically to top it in other ways. You can, for instance, thank Wal-Mart for the trend toward higher-quality groceries, more in-store baking and ready-to-eat gourmet foods, fancier produce, and better delis. These are the ways grocery competitors have differentiated themselves so they can survive against Supercenters.

Wal-Mart has also prodded thousands of manufacturers and suppliers to raise their operating standards. "I've become a better company dealing with Wal-Mart," states Los Angeles toy manufacturer Charlie Woo. "To meet their requests, I constantly have to upgrade my systems and improve my business practices."

The effect is similar to the arrival of Japanese cars a generation ago. Even those of us who have never bought an import have benefited greatly--because the competition they ushered in forced other firms to become much more innovative, and less porky.

The same healthy competition that exists among retailers also operates between different types of communities. The rise of suburbia has forced cities to clean themselves up both physically and in terms of governance. The fresh rural and exurban options now becoming available to many workers--thanks to the Internet and better communication and transportation--will likewise raise the standard for community amenities, and allow more families to live as they like. Places with dysfunctional governments, poor public services, or crumbling physical environments are being disciplined by the voluntary outmigration of residents.

These dramatic evolutions in the way we live, and travel, and shop can be scary, particularly for incumbent politicians, entrenched unions, slow-moving companies, and cities and governments stuck in old ruts. But they open wide opportunities for ordinary people. And that's the nub of today's battle over suburbanization, Wal-Mart, roads vs. rail, and growth vs. stasis. These are more than just skirmishes over what to do with particular plots of land. Demands for strict controls on urban development are part of a wider assault on the highly fluid, efficiency-driven, individual-centered society that has emerged over the last generation.

Horizontal living appalls many partisans of old cities, and those who prefer strong central government, clear social hierarchies, dominant unions, and elite control of urban aesthetics. But sprawl is just one flashpoint. What such people really want is an entirely different kind of economics and politics in this country. As one exurbia basher recently put it in the Boston Globe, "Wal-Mart is not a discount store, it's a wedge issue." The Red/Blue culture wars come home, if you will.

We do our best to map the minefield for you in the pages that follow.

1 comment:

Thanks for the recommendation, Tom. Great articles!

Here's an excerpt from the article How Sprawl Got a Bad Name

By Robert Bruegmann

"Very few people believe that they themselves live in sprawl, or contribute to sprawl. Sprawl is where other people live, particularly people with less good taste. Much anti-sprawl activism is based on a desire to reform these other people's lives."

This is so true. Of course every house adds to urban sprawl. No one's house is exempt. Russ and I were out driving around Pullman yesterday looking at all the new housing developments going up. It was interesting to compare what used to be new, cookie cutter neighborhoods twenty or thirty years ago, now very mature and each house looking different from one another because of the changes and additions by the families who live there.

Post a Comment